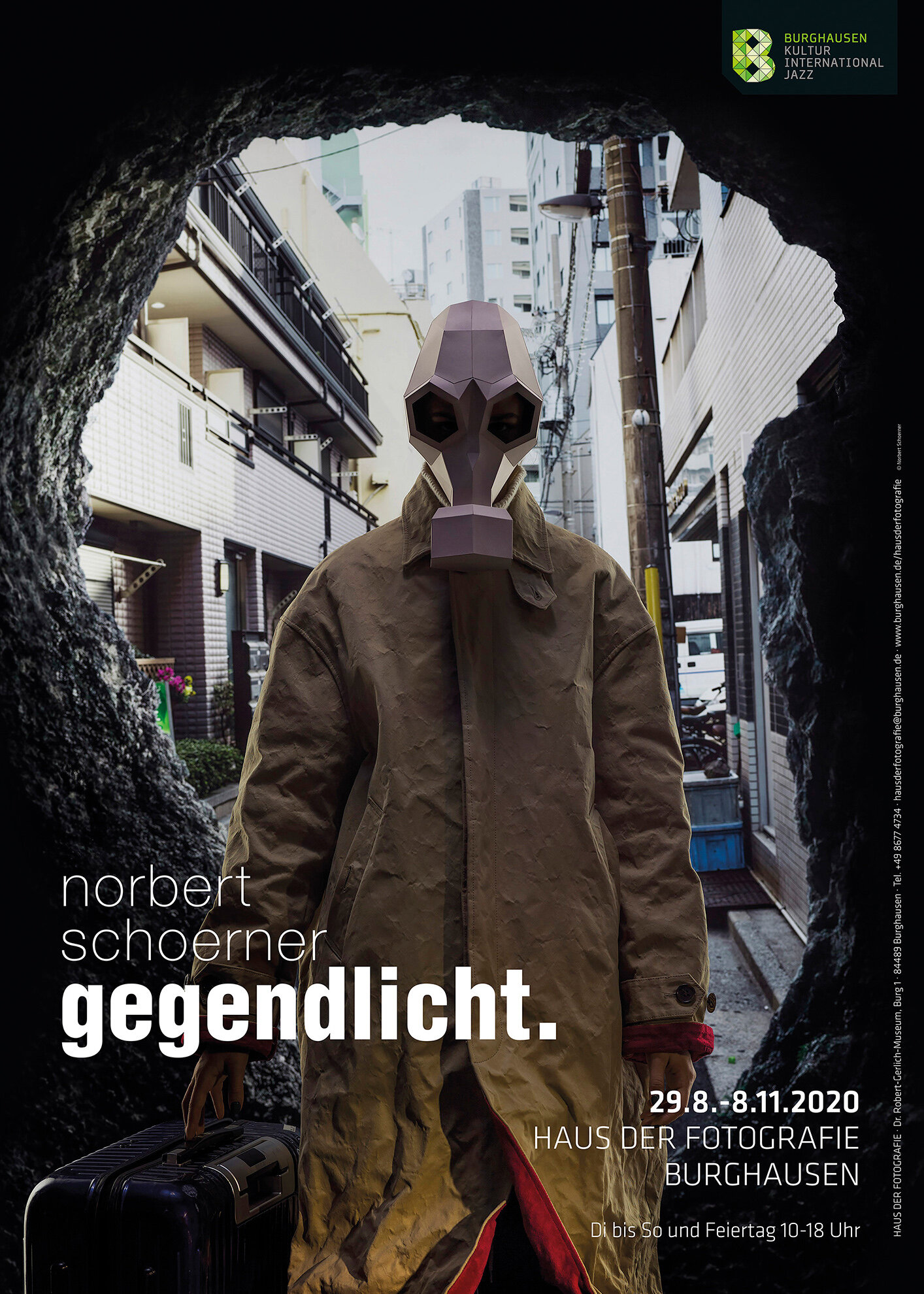

gegendlicht.

In Autumn 2020, the artist Norbert Schoerner and the critic and curator Tom Morton came together to discuss Schoerner’s exhibition ‘Gegendlicht’, then currently on show (with intermittent, COVID-19 related interruptions) at the Haus der Fotografie, Burghausen. Ranging across some twenty years of the artist’s work, their conversation touched on everything from the temporality of photography to landscape and artifice, from the image as a resonant vessel to the liberatory potential of the glitch. Like ‘Gegendlicht’ itself, this discussion focused not on a chronological exploration of Schoerner’s practice, but instead mapped a winding path through it – and one that points, perhaps, to its future direction.

Tom Morton : To begin, can you unpack the title of your exhibition ‘Gegendlicht’, a German word which I believe is a neologism?

Norbert Schoerner: It’s an amalgamation of several words. ‘Gegenlicht’ is the German word for backlight, ‘Gegend’ means ‘area’ and ‘Endlich’ translates as ‘finite’ or ‘finally’. I was hoping that German speakers would initially reflect on the word’s jarring quality, rather than immediately dissecting it.

TM: You’ve spoken about your desire, with this exhibition, to circumvent the idea of a retrospective, describing it instead as a ‘werkschau’ – a term that I don’t think has a direct English equivalent. Nevertheless, the show gathers together still and moving image works made over a period of roughly 20 years

NS: ‘Werkschau’ is an important term in German language-based curatorial practice. I did, unsuccessfully, try to find a suitable English translation of the word. It’s different to a retrospective, which would present a more comprehensive and perhaps chronological approach towards a body of work. This wasn’t my intention for ‘Gegendlicht’. Here, I wanted to bring together works from different periods, creating new (and at times pretty abstract) bridges between this fragmentary, potentially incongruous material.

TM: It feels important to mention that several of the works at the Haus der Fotografie emerged from magazine commissions. I’m struck by how the selection refuses to draw firm distinctions by what some people might classify as ‘commercial’ and ‘non-commercial’ modes of working.

NS: As you mention, there’s a classificatory impulse in cultural politics, which has to do with creating a framework for critique. Several of the works in the show did originate from magazine commissions, but somehow, because the publications in which they appeared gave me complete creative freedom, I’d never consciously categorize this work as ‘commercial’.

TM: Perhaps we’re better off thinking about such commissions as simply an opportunity to create an image?

NS: I’d say that my practice has always existed in an opaque no-man’s land. The lines are definitely blurred.

“I’d say that my practice has always

existed in an opaque no-man’s land”

TM: The first camera phone (the Kyocera Visual Phone VP-210) was released in Japan in 1999. Over the next two decades – the same 20-odd years tracked by your exhibition – the way photographic images are created, circulated and consumed was utterly transformed, owing in large part to the mainstream adoption of this technology. To what degree does ‘Gegendlicht’ reflect on this transformation? How do you as a photographer locate your practice in a world where billions of people carry a device in their pocket that can take, edit, share, and receive feedback on photographic images with unprecedented ease?

NS: My practice consists of an ongoing exchange between craft and theory. This process is often slow, and is to a degree empirical, containing various analogue stages. In that sense I’ve not been too affected by the mass market’s fast-sharing culture and re- categorisation of images as multi-platform assets. My 2012 book ‘Third Life’ set out to explore aspects of that then-emerging evolution. Now I’m mainly interested in the challenge of creating photographic work that resonates in an ongoing, expanding manner, suspending the viewer’s troubled attention span.

TM: That’s a fascinating idea. Several contemporary painter friends have spoken to me about their desire to make works that at least temporarily recalibrate the viewer’s visual attention, eliciting a ‘way of seeing’ that’s much more mindful than our acquired habit of scrolling and swiping through mass culture imagery. In short, a kind of ‘slow painting’. Do you practice ‘slow photography’?

NS: Yes. Obviously, my images aren’t made to be presented within the template of a social media app. Then again, no contemporary visual artist can escape from becoming potential scrolling bait! Nowadays, the ubiquitous modus operandi for experiencing art is obviously the on-screen display. This is can often be an issue for the work – the compressed scale erasing the subtlety of the details is just one example. Not to sound too archaic, but for me the ideal presentation for most photography is the printed form.

I find your term ‘slow photography’ very interesting. It’s very much reminiscent of experiences I had while working on my current project ‘The Nature of Nature’, which is in part a collaboration with a Bonsai master from Fukushima in Japan. Some of the images in the series are the result of 5-10 minutes exposures at night – one could say the opposite of a snapshot. The Bonsai master’s appreciation and understanding of time is completely different to anything I’d encountered before, and it made a very deep and lasting impression on me. While I was exposing the images, in complete darkness, it became clear to me that my approach might be a subconscious response to the seemingly infinite time line of the master’s practice of sculpting the Bonsai. This reflection on the meditative aspect of the Bonsai work is in its own way a version of ‘slow photography’.

“Now I’m mainly interested in the challenge of

creating photographic work that resonates in an ongoing, expanding manner, suspending the viewer’s troubled attention span”

TM: I’m intrigued by the staging of the 11 works which share the title Assemblage (2020), and all of which are – in their different ways – an essay in shadows. Installed along the length of a corridor, they’re glazed in highly reflective Perspex, an unusual material to employ in a photographic exhibition, where it’s customary to glaze works using museum glass in order to minimize reflections, helping the viewer focus on the work rather than their own mirror image. Then there’s the fact that the facing wall is painted black, as if to suggest that the viewer is emerging from a shadow. Can you tell me more about this set of decisions?

NS: I’m very fond of this part of the exhibition. It’s partially a result of working with the spatial challenges of the Haus der Fotografie. The corridor used to be a small backstage area – this part of the museum used to be a venue / performance space. It’s somehow claustrophobic in character, presenting an interesting challenge during the installation of the show. The space felt perfect for ‘Assemblage’ – an almost monochromatic series with strong shadow elements. We augmented the corridor with black wall segments and used glossy, almost mirror-like mounts which, when viewing the prints, would immerse the audience by including their own reflections.

TM: There’s some interesting things going on, here, with time. Seeing our image reflected back to us in the mounts, we become aware that the faces of previous visitors have been mirrored in the Perspex before we stood in this corridor space, and those of future visitors will be after we leave, almost as though the installation was a surveillance system, like the black box of a flight recorder. Then there’s the way in which it disturbs the temporality of photography. If the still image is a frozen lake, then these reflections are anomalous ripples on its surface...

NS: In his book ‘The Ongoing Moment’ Geoff Dyer creates a fictional narrative where various famous photographers would constantly encounter each other through the subject matters they photograph, creating an ongoing, never-ending thread of meaning. This inspired in me the idea that a photograph should not be seen as a hermetic representation of a frozen moment, but a resonant vessel, with ever-expanding meaning. By working with the Perspex, we added a reflective membrane between the viewer and the surface of the print, in order to draw the outside world (and with it the viewer) into the image, a ripple of another layer of reality. Might we consider this a form of osmosis?

TM: Your show features a music video you directed for UNKLE’s 2017 track The Road. Here, a camera fixed to a drone swoops over a highway that slices through a nocturnal American desert landscape, dotted with boulders, scrubby trees, and a collection of derelict buildings and abandoned trailers – all that remains of the ‘ghost town’ of Cisco, Utah, a location that features in Richard C. Sarafian’s 1971 movie, Vanishing Point. One of the most striking things about this footage is that the lights attached to the drone – which have the feel of both a police helicopter’s search beam, and a UFO scanning the Earth’s surface – illuminate this landscape in such a way that it feels more like a meticulously fabricated model than a genuine location. Was this intended? There’s an interesting tension between the diorama-like appearance of Cisco in the video, and the track’s repeated lyric: “Is it real / I believe it when I feel”.

NS: My initial idea for the video was inspired by the title of the song. I wanted to work with an archetypical American landscape, use it as a backdrop for a post-road movie and challenge traditional perceptions of the ‘road’ being a trajectory towards freedom. By chance we came across a guy in Utah, USA who had developed a drone carrying the equivalent of a 10k HMI (a very strong light source used, for example, to light up whole streets in movies). We decided to go and see him in Salt Lake City. Once we started testing the light with him we realised that, pending the angle of the camera fixed to the drone, a tilt shift effect occurred, which created a drastic compression of the landscape, deducting any scale references. In another bout of luck, while scouting for locations in Southern Utah, we came across Cisco – the cathartic final location of Vanishing Point, one of my favourite road movies.

TM: Landscape is, of course, an abiding preoccupation in your work. What draws you to the locations you photograph? How do you position your landscape pieces in the genre’s history?

NS: I’m inspired by portraying a ‘natural’ environment, a landscape, by submerging it in a subtle layer of artifice. This can happen through lighting, a sense of illumination, or by re-staging narrative elements already present in a location. The aim is to show familiar concepts in a non-literal way, to find moments in-between reality and fiction, between the tangible and one’s imagination.

TM: ‘Gegendlicht’ features a single abstract – or seemingly abstract – photographic work, Debase (2020), which at a distance might be mistaken for a modernist painting, or else a corrupted image file. Can you tell how this piece came into being?

NS: Debase is part of a body of work consisting of ‘corrupt’ images. What interests me about the idea of digital errors is that they present a contradiction to the idea of the machined perfection of the digital process. Can one regard this type of ‘accident’, the mere randomness of it, as an act of fate? Or possibly even read it as a transcendent analog intervention caused by a ghost in the machine? It’s also worth considering the potential of parallels to analog photography. There, chemical compounds or a light spill would cause the accidental abstraction.

TM: It’s notable that you mention the concept of accident (and its deterministic counterpart, fate), which reoccurs through the history of photography. I’m sure we can both quote numerous seminal photographers on the part chance has played in the capturing of their most famous shots. Is digital error just another type of contingency for the photographer to navigate, and potentially exploit, like the light conditions on a given day, or the action on a given street? Might we think of it as an ‘event’, or even a ‘post-event event’? Then of course there are questions of authorship. Is this work a collaboration of sorts between you and a (glitchy) artificial intelligence?

NS: I don’t necessarily think that one should consider the contribution of the machine as authorship per se, but it certainly points at interesting questions in relation to the idea of failure within a seemingly perfect system – the previously mentioned self-contained reality of a machined environment. Possibly even a visualisation of a ‘Syntax error’? Your proposition of the post-event event is also really interesting in that context. Just like a moment, the glitch represents something unique and not repeatable. It challenges the idea of photography’s role as a method to record this perceived uniqueness. Beyond that, I’m inspired by the idea that a corruption is symbolic of a ‘reset’ – when all referential frameworks and aesthetic associations start to fragment. Maybe this could help us to escape from the permanent feedback loop of a stale reference culture? Mark Fisher wrote that ‘the correlate of a future that will not arrive is a past that won’t disappear’. I find this rather brilliant, especially in the context of the corrupt imagery. Is it time for us to reinvent our societies and ourselves in order to create possibilities for a new future? Maybe the glitch can save us.

Museumleitung

Ines Auerbach

Ausstellungsinstallation

Franz Ramgraber

Installation Images

© Norbert Schoerner

© Gerhard Nixdorf